While hiking in the Lake District, I was constantly enveloped in English. Every signpost was in English. Every hiker I met spoke English. So, it happened that I began to speak and think in English as well. Some of the sentences of this text just created themselves in my mind while I walked and I began to make notes in English. Finally, the idea began to take shape, not only to make my first Wainwright, but to write about this journey in English.

It is an attempt. Even if I still lack a feeling for the words in a language that is unfamiliar to me. In German, it’s easy for me to play with words and invent unconventional combinations like ‘herbstbuntlich’ (painted in all the colours of autumn). In English, I have to rely on a hopefully correct sentence structure and don’t take any risks. Furthermore, Alfred Wainwright is virtually unknown in Germany and the idea of “collecting Wainwrights” is of no interest to the German reader.

So, this is how I made my first Wainwright.

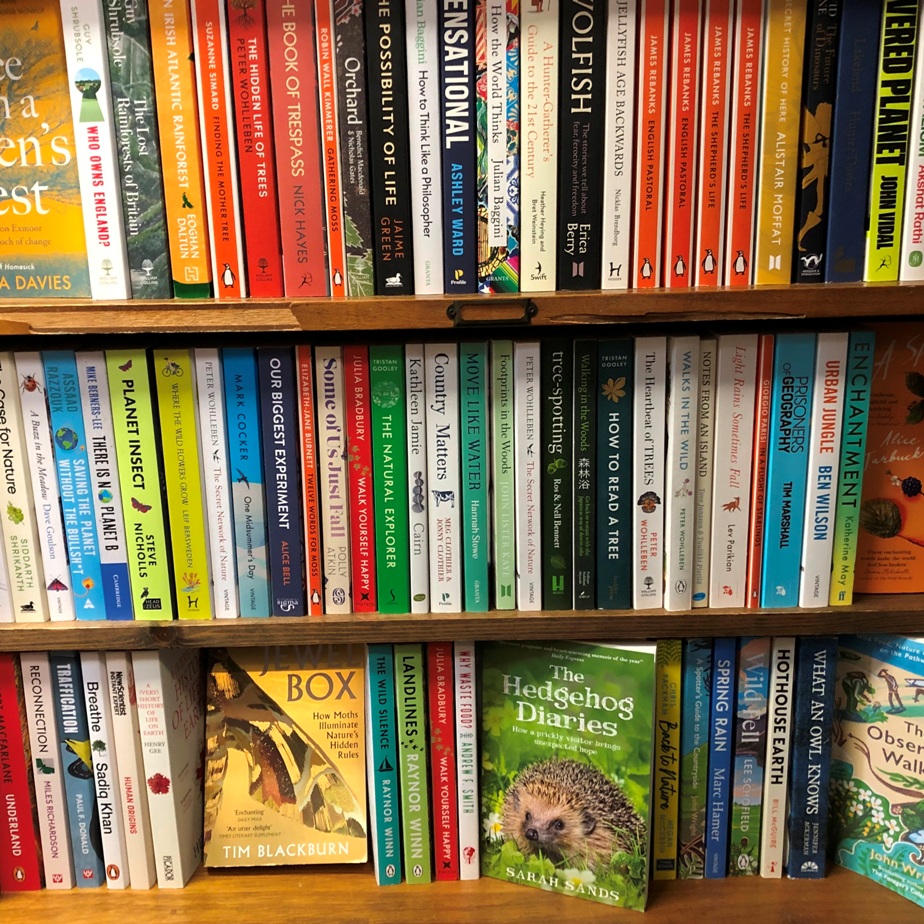

I was surprised at how many hikers were out and about in the Lake District and I learned that “making wainwrights” is a well known leisure activity. My special thanks go to Rydal Hall for a really perfect cabin (which could do with a little better lighting), to all the unknown hiker who helped me with their advice or just gave me a smile on the way and to Fred’s Bookshop where I found more books about nature / nature writing than in any bookshop I visited in Germany.

Loughrigg Fell

The day starts in the rain. Towards morning, I sleep badly because I hear some kind of noise. Later I realise that it is the rain dripping from the roof of the cabin, separated from me only by a thin wooden wall. Now it’s time to make some tea and light the small wood stove that warms the cabin. Unfortunately, lighting the fire is a pain. But with a second attempt and a little persuasion, it works. Today I want to reach Loughrigg Fell. I like the fact that I can start right here. I don’t have to go for an intermediate destination by car first.

While I wait for the kettle to whistle, I look out over the landscape. The rain clouds hang low over the landscape. Smoke is also curling out of the neighbouring cabin, about 50 metres away. I feel sorry for the campers staying here in tents. It is very late summer, more like autumn. The nights are cool and the meadow around the tents is damp from the rain. I’m glad to have permanent accommodation.

As I start my walk, I realize the difference between a walk at home within my usual landscape and here. It is much more like an adventure, even if my challenge is only a cold cabin in the morning. I know, I am very far away from Elise Wortley, who walked the Cairngorms using equipment and clothing of Nan Sheperds time. Nevertheless, I now understand better, what it makes to a mind and a body, if the conditions change.

On the first half mile I meet some of the campers, who I felt sorry for an hour ago because they spent the night in the cold. They are perfectly equipped and cheerful. Walking in a chilly, rainy morning seems nothing special for them. Further on the way to Rydal Cave, the first stop for today, I see all types and ages of hiker. Young people in shorts as well as older ladies in elegant clothing and waterproof hiking boots.

I don’t understand how all these people find the way to their goal. The paths are incredibly poorly signposted. Right at the start of my route, at the bridge over the little river Rothay, there is a ‘public footpath’ sign. That’s nice to know, but it only means that it is permitted to pass through this gate. Where the footpath leads remains a mystery.

A path to Loughrigg Fell is supposed to branch off near Rydal Cave, but I can’t find any path at all near the cave. Something branches off a long way before the cave, but I think that’s wrong. The hiking app is clearly unable to cope with the situation. Finally, I dig Wainwright’s book out of my rucksack. It has directions and sketches for the entire tour on a single page. I read in the biography of Wainwright that the books are still popular today because they show exactly the details that are needed. And so it is. Only in this book, which is now 80 years old, can I recognise that I have to look for a path that branches off to the left of a creek before the first cave. There is actually a path there! These are exactly the details I need. As I follow the barely visible path, I wonder how Wainwright managed to find his way here without his own book.

The path leads steadily uphill. It is narrow, muddy and overgrown waist-high with ferns. I wait for a junction where I can use the further information from Wainwright. There is supposed to be a sacred tree where I have to keep right for a short time. There is no junction. I follow the path. There is no other.

After a while, a hiker comes towards me. He comes from Loughrigg Fell, he says. He only knows this path. In a few hundred metres there is a gate and a path running across it. I walk on. The path becomes narrower and even muddier and finally reaches the top of the pass, which is marked with a stone pyramid. There is no cross-path to be seen for miles around.

I’ve been travelling for barely more than an hour and am lost in the middle of nowhere. The path is barely recognisable. Ferns in all directions and, further up, bare hills. I’m sure I’m on the wrong path and scan the area with an insistent gaze to see if I can spot a path or even just a structure that stands out from the endless bracken.

Finally, no structure, but people. Two hikers come towards me. I am also caught up by two young people. Quite a lot going on, on my fern trail through the wilderness. Conversation reveals that the oncoming hikers don’t know the way either. And those following me strongly advise against taking the path through the ferns. But none of the people seem unsettled. After a friendly chat, they all walk on confidently in one direction or another. How different it is to deal with lost paths.

A little later, I find the crossroads I was told about and suddenly it’s really busy. Where have all these people come from? A little further on towards Loughrigg Fell, the path is suddenly signposted with a blue arrow and sporty people of all ages run past me. The athletes run past me at a brisk pace, splattered with mud, in shorts and almost without luggage. I’m glad I have a jacket and food.

The summit is just as busy as Rydal Cave. An incredible wind is blowing. There’s hardly a place where it doesn’t blow me away. It’s too crowded and too windy to have a leisurely cup of tea. Some group celebrating their fifth anniversary asks me for a group photo. The runners with the blue arrow only stop briefly and hurry on.

I also soon walk on to Loughrigg Tarn. Three neighbouring lakes can be seen from the summit. Loughrigg Tarn has no neighbours. Seen from the summit, it is probably hidden behind one of the surrounding hills. Once again, there is no signposting. I follow the path that I find most realistic in the app. The path is incredibly steep and slippery. It’s more of a scree slope than a path. But the path remains visible and follows the app exactly.

I now think that the lines shown in the app are not paths at all. Some hiker is walking cross-country through waist-high ferns and reaches his destination by chance. This is displayed as a route and other people walk through the middle of the wilderness because they believe the app more than their own eyes. At some point, so many people have trampled the wilderness that a new path has actually been created.

It’s only when I’ve descended quite a way that I remember that I wanted to take a photo with Wainwright’s book at the summit. It’s a shame, I’m annoyed that I forgot to take the photo. Especially as it will probably be my only Wainwright summit. Yet, I’m travelling for myself, not for a photo album. I’m enjoying the landscape and want to experience as many facets of it as possible. I’ll soon be back home again and will look back longingly on my time here.

Loughrigg Tarn

When I reach the Tarn, I find a path that actually leads directly to the shore. Phew, now it’s time for a proper break. I unpack my teapot and sandwich and enjoy the view of the lake in the sunshine.

After picnicking for a while, I think about which route to take back to Rydal. On the map I find a narrow path which, after a wide arc around Loughrigg Tarn, leads off the road to Ambleside. From there it’s only 2 miles to the cabin. I’m surprised at how few kilometres I’ve only covered. About half of the route planned for today is behind me. And yet it already feels like an extensive hike.

First, I cross a meadow with a flock of sheep to get to the new path. The path through the herd of sheep is also signposted as a public footpath. I am surprised at how timid the sheep are. I had expected, or rather feared, that the sheep would be so used to people that I would be surrounded by them on the path across the meadow. The opposite happened. As soon as I open the gate, they move out of the way and give me space.

The new route is initially a tarmac country lane, signposted as a regular minor road. The lane is barely wider than a car and, as with almost all roads here in the Lake District, there are hardly any opportunities to stop. I therefore enjoy the perspective all the more as a pedestrian. I stroll through the illustrated book Lake District. A new page is turned again and again: Loughrigg Tarn, Skelwith Bridge, Skelwith Fold, Brathay Bridge.

At Skelwith Bridge, I meet the blue arrow runners again. The route runs a short distance along the busy A593 to Coniston to cross the Brathay. The roadside is packed with runners‘ supporters and the organiser’s stewards alerting motorists. Here I finally find out what the competition is all about: the race is called ‘The Lap’ and runs for 45 miles around Lake Windermere. Unbelievable!!! Such a long route and about 6500 feet of elevation gain. And there are lots of runners of all ages. I, on the other hand, walk just 10 miles over a single summit and take the whole day to do it. I’m almost embarrassed to take the same route as the athletes and possibly throw one of them off their rhythm.

Ambleside

In Ambleside, I go to the bookshop that was recommended to me at the post office in Windermere. I am surprised to see that there is a whole shelf of nature books. Everything I have on my reading list and have painstakingly collected is here in one place. And yet the bookshop is tiny. The much larger bookshops near my home don’t stock a tenth of these books.

The bookseller gives me the tip to take the cycle path for the last stretch back to Rydal. It’s easier to walk than the hiking trail and still far away from the road. Once again, I get to see things that would otherwise only whizz past the car window or remain completely hidden from me. I would never have seen the stepping stones across the river otherwise.

Shortly before Rydal, I have to change to the country road. There I meet an old man with a gap in his teeth and a crooked hat. He is pulling a trolley case behind him while an even older woman accompanies him. It’s a scene straight out of Hundraåringen som klev ut genom fönstret och försvann (The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared). Have I stumbled into a British remake of the Swedish film? After this last encounter for the day, I’m glad to be back in my cabin.

Within only 10 miles I have experienced completely different landscapes and moods:

– Tourists and excursionists at Rydal Cave

– Solitary hiking through the bracken

– Sporty liveliness on the windy summit of Loughrigg Fell

– Autumn sun at Loughrigg Tarn

– The hustle and bustle of Ambleside

For dinner, I have fish and chips from Ambleside. I put one of the cabins LED lights on my thermos flask and sit over my notes for quite a while. I’m always surprised at how many experiences and thoughts I can fit into a single day.

As I think back to the path through the bracken and the view from Loughrigg Fell, the little stove howls plaintively to itself. A piece of the seal on the stove door is missing. As soon as I close the door, the stove starts to howl. Should I put some wood on to keep it warm for as long as possible? Or is it better to let it go out so that I can sleep?

Lake District, September 2024